|

John Baskerville

Wolverly 1706 - London (?) 1775

|

John Baskerville è il tipografo-editore inglese del '700 che ha inventato l'editoria moderna, sperimentando rilegature, inchiostri, carte e tecniche di stampa innovative e disegnando un set di caratteri che è ancora oggi uno dei più eleganti e leggibili mai realizzati.

Egli fu infatti un grande rinnovatore nell'arte tipografica e rappresentò il primo esempio di editore nel senso moderno del termine.

Il nostro centro studi e la casa editrice Baskerville sono dedicati alla sua curiosità, al suo spirito creativo e alla sua perseveranza sognatrice in perfetto spirito illuminista che ha saputo trasformare la tecnica della stampa e l'arte tipografica nell'a moderna attività editoriale.

John Baskerville è nato il 28 gennaio 1706 a Wolverley, vicino a Kidderminster, nel Worcestershire, ed è stato tipografo a Birmingham, Inghilterra.

Membro della Royal Society of Art, dopo aver insegnato calligrafia, si occupò come tipografo ed editore di composizione della pagina, di carta e di inchiostri. Sperimentò tecniche diverse di legatura dei volumi e di stampa al torchio tipografico e applicò al disegno e alla fusione del carattere da stampa il suo genio formale guidando il lavoro del suo incisore John Handy della preparazione dei punzoni del carattere che ha il suo nome: il Baskerville.

Nel 1758 fu nominato, per la sua attività, tipografo ufficiale dell'università di Cambridge e, nel 1763, pur essendo ateo dichiarato, pubblicò una splendida Bibbia in folio ma la sua eccentrica natura lo portò a concentrare i suoi interessi nell'attività di editore, attività che non lo ricompensava delle energie spese.

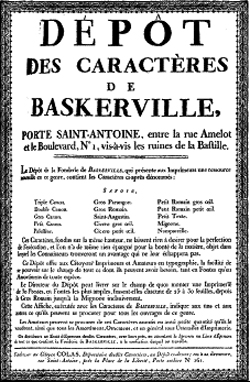

Tentò infine di vendere i suoi caratteri alle Stamperie Reali, all'Accademia delle scienze di Parigi, alla corte di Russia e di Danimarca, con scarso successo.

Morì in circostanze misteriose e mai del tutto chiarite (forse a Londra nel 1775).

Ancor oggi si sa poco della sua fine e deve essere ancora scritta la sua biografia completa.

Triste storia per il vero padre della moderna editoria.

|

|

"NON E' MIO DESIDERIO STAMPARE MOLTI LIBRI, MA SOLO QUELLI IMPORTANTI O DI MERITO INTRINSECO E DI SICURA FAMA CHE IL PUBBLICO POSSA COMPIACERSI DI VEDERE IN ELEGANTE VESTE TIPOGRAFICA E DI COMPRARE AD UN PREZZO CHE COMPENSI LA STRAORDINARIA CURA CHE NECESSARIAMENTE SI DEVE FISSARE PER ESSI".

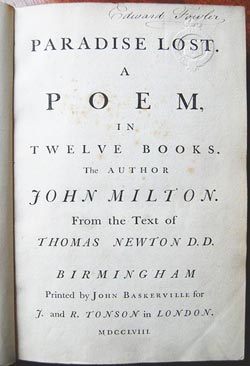

(dal frontespizio della sua edizione del Paradise Lost di Milton).

I suoi caratteri, dopo la sua morte, vennero ripetutamente venduti e se ne persero le tracce.

Vennero utilizzati durante la Rivoluzione Francese ("Le moniteur universe") ma non rimane traccia dei ripetuti passaggi di tipografi che subirono.

I suoi caratteri furono molto ammirati da Benjamin Franklin che li introdusse negli Stati Uniti e che furono adottati da molte pubblicazioni istituzionali che ne sancirono il successo nel nuovo mondo.

Nel 1917, Bruce Rogers (consulente grafico dell'Università di Cambridge) riscoprì e rivalutò l'opera e la personalità di Baskerville.

Nel 1953 infine Charles Peignot fece dono dei punzoni sopravvissuti all'università che lo ebbe come tipografo ufficiale.

Baskerville non è solo il grande riformatore della stampa inglese del suo tempo, ma esercita una duratura influenza sia nel disegno del carattere che nella attività editoriale dei secoli successivi.

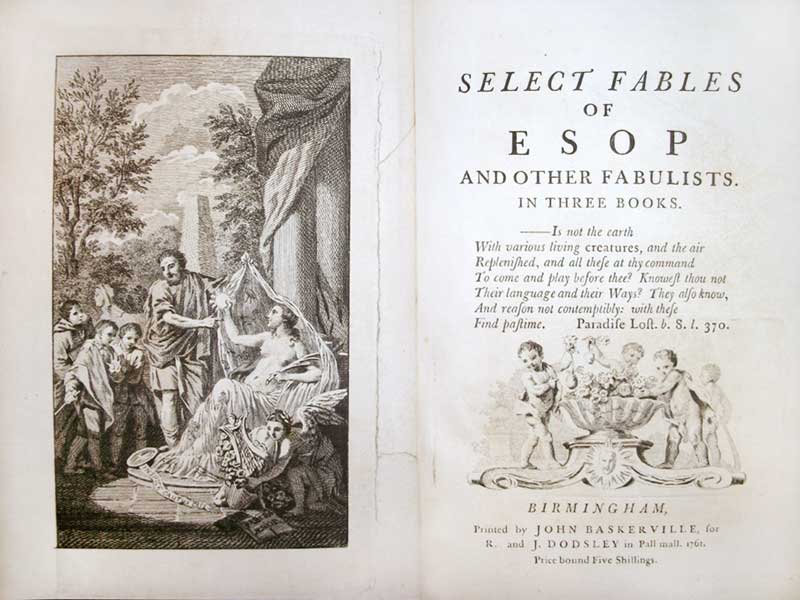

Uno dei suoi principali contributi alla stampa moderna è la sua insistenza sulla possibilità di produrre un bel libro per mezzo della pura e semplice tipografia. Quest'idea, diventata ormai luogo comune, era invece rivoluzionaria in tempi in cui un libro veniva apprezzato in base alle illustrazioni, alle incisioni, o alle rilegature in pelle e in cui le grandi biblioteche si vantavano di non avere che manoscritti.

Baskerville è stato il primo editore della storia e lo ha fatto prestando molta attenzione alla qualità del suo lavoro, con uno spirito innovativo e una cura tali da produrre un'arte che nei secoli successivi non ha più avuto altrettanta pregevolezza.

---------------------

(da Wikipedia)

Baskervillle was born in the village of Wolverley, near Kidderminster in Worcestershire and was a printer in Birmingham, England. He was a member of the Royal Society of Arts, and an associate of some of the members of the Lunar Society. He directed his punchcutter, John Handy, in the design of many typefaces of broadly similar appearance.

John Baskerville printed works for the University of Cambridge in 1758 and, although an atheist, printed a splendid folio Bible in 1763. His typefaces were greatly admired by Benjamin Franklin, a printer and fellow member of the Royal Society of Arts, who took the designs back to the newly-created United States, where they were adopted for most federal government publishing. Baskerville's work was criticized by jealous competitors and soon fell out of favour, but since the 1920s many new fonts have been released by Linotype, Monotype, and other type foundries – revivals of his work and mostly called 'Baskerville'. Emigre released a popular revival of this typeface in 1996 called Mrs Eaves, named for Baskerville's wife, Sarah Eaves.

Baskerville also was responsible for significant innovations in printing, paper and ink production. He developed a technique which produced a smoother whiter paper which showcased his strong black type. Baskerville also pioneered a completely new style of typography adding wide margins and leading between each line.[1]

Baskerville, an atheist, was buried at his own request upright, in unconsecrated ground in the garden of his house, Easy Hill. When a canal was built through the land his body was placed in storage in a warehouse for several years before being secretly deposited in the crypt of Christ Church (demolished 1899), Birmingham. Later his remains were moved, with other bodies from the crypt, to consecrated catacombs at Warstone Lane Cemetery. Baskerville House was built on the grounds of Easy Hill.

---------------------

(dall' Enciclopedia Britannica)

John Baskerville

(1705 ?- 1775)

He was accused of being eccentric for his unrelenting perfectionism. Accused of being immoral for flaunting social conventions. And, most injurious to him, accused of creating type that was "unattractive and painful."

Before John Baskerville decided to transform his love of letterforms into an amateur pursuit, the art of book-printing and type-creation had remained essentially unchanged since Gutenberg's time.

Baskerville turned the creative process on its head:he designed his namesake typeface not in accordance with the technological capabilities available to him, but rather to suit his particular aesthetic sensibilities. He then proceeded to redesign the printing press, papermaking and paper-finishing to accommodate the reproduction of his type.

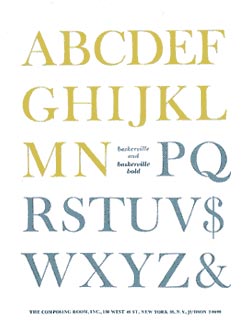

Baskerville's type was unlike anything that had come before it. Considered by contemporary historians to be the quintessential example of a transitional face, it featured rounded characters, a perpendicular axis, strong contrasts between thicks and thins and very fine, sharp serifs, all of which clearly distinguished it from the old-style faces it followed.

John Baskerville started his professional career as a parish school writing master and later became a headstone engraver, two professions which allowed him to demonstrate his manual dexterity and technical proficiency. However, it was in japanning the craft of covering metal household items with multiple coats of varnish and finishing them with decorative paintings that he made his fortune. When he turned his attention to type and printing, he was already a successful businessman.

He therefore had the luxury of working at leisure, and this freedom allowed him to indulge his fanatical meticulousness. It took John Baskerville six years to complete the drawings for his type and another two to oversee its cutting. When finished, he discovered that conventional printing presses could not adequately capture its subtleties and redesigned his own. In place of wood, he used a machined brass bed and platen and a smooth vellum tympan (a sheet that was placed between the impression surface and the paper to be printed) packed with fine cloth to ensure that the two planes of the press met more evenly.

Most paper used in the mid-18th century was made on crude wire mesh molds that left deep vertical ribbed impressions. This too was unsuitable for capturing the delicacy of Baskerville's type.

Setting up a mill on his own land in Birmingham, Baskerville manufactured what we today refer to as wove paper, made on very fine meshes that resulted in smooth, silky stock. To further polish its surface, he created a device consisting of two heated copper cylinders between which he pressed his paper after printing it.

John Baskerville is frequently referred to as the inventor of wove paper, although there is evidence that others used it before him. What is known is that he was greatly envied for his inks. During the period in which he lived, printers made their own inks, and their proprietary formulas were highly guarded trade secrets.

Baskerville invented an ink that was both quick-drying, allowing him to print the reverse sides of his paper faster, and uncommonly rich, black and lustrous in appearance.

Baskerville's insistence on doing things his own way was manifested in all areas of his life. For many years he lived with a woman who, while abandoned by her husband, was still legally married to him (though it should be noted that when Sarah Eaves' husband died, John Baskerville married her without delay). He was a proud man, one who did not feign humility about his technological achievements. And perhaps most damning, he was a vocal and highly critical agnostic.

While printers and type founders in England claimed that the combination of fine type printed on smooth, reflective paper made his books difficult to read, John Baskerville's efforts were praised by his peers in both Continental Europe and the United States. Printing and typographic luminaries no less than Ben Franklin and Giambattista Bodoni were great admirers and lively correspondents.

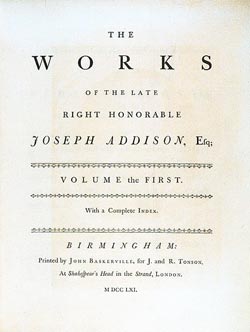

Unfortunately, encouragement alone was not enough to prevent Baskerville from losing a considerable amount of money on his hobby, and after creating his masterpiece, a folio bible printed for Cambridge University in 1763, he spent the remainder of his life trying to dispose of his equipment. Four years after his death, Baskerville's wife sold it to a French dramatist who used it to print the works of Voltaire in Germany, then brought the punches and matrices with him to France. They changed hands many times, losing their value as popular taste in type moved away from classic faces. However, the classic roman type revival in the beginning of this century lead by England's Lanston Monotype Corporation resulted the successful introduction of Baskerville to a new era of book designers in 1923. Thirty years later, the Paris type foundry Deberny et Peignot was the penultimate in a long succession of Baskerville's original punches to the Cambridge University Press as a gesture of goodwill. After almost two centuries of neglect, Baskerville's handwork was back on English soil and his type universally appreciated for its beauty, elegance and versatility. |

|

| |

Dal sito di Birmingham "Explore the Birmingham Jewellery Quarter"

John Baskerville was born in 1706 at Wolverley in Worcestershire. He was a man with a lifelong passion for beautiful lettering and books. By 1723 he had become a skilled engraver of tombstones and was teaching writing. He moved to Birmingham in about 1726 and set up a school in the Bull Ring where he taught writing and book-keeping, whilst still maintaining his work as an engraver. In 1738 he set up a japanning business in Moor Street (japanning was an early form of enamelling), in which he first showed his mettle as an innovator, ‘effecting an entire revolution’ in the manufacture of japanned goods, and specialising in salvers, tea trays, bread baskets and the like. Within a decade he had become a wealthy man and had bought an estate of some eight acres and a large house on the site of the present-day Baskerville House.

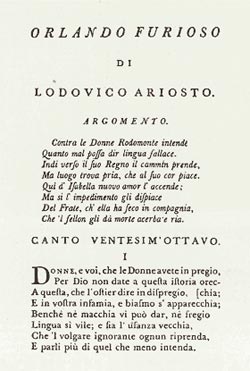

Whilst keeping on his japanning business, in about 1750 he once again turned his attention to his passion, typography. He experimented with paper-making, ink manufacturing, type founding and printing, producing his first typeface in about 1754. Never afraid to innovate, he made changes to the way in which metal type was made, enabling him to produce finer, more delicate lettering than any before him had achieved. He invented his own lustrous, uniquely black, opaque ink; he was the first to exploit commercially James Whatman’s invention of wove paper, which was much smoother than the traditional laid paper; and he modified the printing process by using heated copper cylinders to dry the ink before it had time to soak too far into the paper. All of these innovations enabled Baskerville to produce printed work of an elegance, crispness and clarity never seen before.

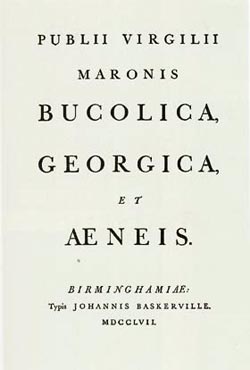

In 1757 he published his first book, an edition of Virgil. This was followed by some fifty other classics. In 1758 he became printer to the Cambridge University Press for which, in 1763, he published his masterpiece. Ironically for a confirmed atheist, his greatest work was a folio edition of the Bible, which. represented a monumental advance upon the standards and practices of the time. He established a lasting friendship with the American scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin, who had built up a successful printing business in Philadelphia, and who visited Baskerville in Birmingham.

John Baskerville’s guiding principles in his work were simplicity, elegance and above all, clarity. The typeface that bears his name remains one of the most pleasing of the all-time great classical fonts, vastly superior to the dismal Times Roman which, sadly, has become all too ubiquitous. (If you're lucky enough to have John Baskerville's font installed on your computer, you will be reading it right now.)

John Baskerville was a friend of the Boulton family, and a good friend and mentor to the young Matthew Boulton as he was growing up. Defying convention, he lived openly with his partner, Sarah Eaves, whose husband had deserted her; rejected religion, pouring withering scorn upon religious bigots; and indulged his fondness for show, wearing masses of gold lace and riding about in a lavishly decorated carriage (see right hand panel).

John Baskerville died in 1775 and was buried in a little mausoleum in his garden. As to what happened next, I am most grateful to Deborah Cooper for allowing me to publish below her account of the bizarre travels of John Baskerville's body, which is one of the most complete accounts I have seen.

Strange but true – extract from ‘John Baskerville – a man with a mission’

by Deborah Cooper

Aris’ newspaper carried this news on 23rd January.1775 – "Died. On Monday last, at Easy Hill in this Town, Mr John Baskerville; whose memory will be perpetuated, by the Beauty and Elegance of his Printing, which he carried to a very great Perfection."

Baskerville died in January 1775 at the age of sixty-nine. He was followed thirteen years later by his partner Sarah and they left no heirs. It was left to an American to discover the genius behind the designs that he had spent so many years perfecting. His personal crusade was finally won when he was recognized, albeit posthumously as one of the greatest type designers that ever lived. It was a fitting memorial to a great man whose typeface is still in use today. Renowned for his attention to detail and his tenacity in the face of obstacles, one would suppose that when he was finally laid to rest in a mausoleum in his own grounds, as requested, with a seemingly proper appreciation at last of his life’s work, he would finally find rest, with nothing left to strive for. However, as far as John Baskerville was concerned, even in death he was destined to be unsettled with where he was put.

After Sarah followed him to the grave on 21st March 1788 Baskerville’s house was sold to John Ryland who then moved in 1791 after it was attacked and wrecked during the Birmingham riots. On his death Ryland left the house to his son, Samuel. Samuel demised it to Thomas Gibson who cut a canal through the grounds and converted the rest of the property into wharf land. Unfortunately the intended route for this canal lay directly through the mausoleum and the decision was made to demolish the building to make way for it. The body, however, lay undisturbed beneath. Later on though, in 1821, the lead coffin was discovered by workmen digging for gravel and a few days later it was disinterred.

Nobody came to claim the coffin and contents and because of Baskerville’s atheism he could not be interred in Holy ground in the local cemetery. For want of somewhere to put them, the coffin and its contents were deposited in Messrs. Gibson & Sons warehouse in Cambridge Street (it seems ironic that Baskerville should be stored on a street bearing the same name as the university for whom he was Master Printer for ten years). According to writings by Langford: "a few individuals were allowed to inspect it. The body was in a singular state of preservation, considering that it had been underground about 46 years. It was wrapt in a linen shroud… The skin on the face was dry but perfect. The eyes were gone, but the eyebrows, eyelashes, lips and teeth remained. The skin on the abdomen and body generally was in the same state with that of the face. An exceedingly offensive effluvia, strongly resembling decayed cheese, arose from the body and rendered it necessary to close the coffin in a short time".

The coffin was left in Gibson’s warehouse for the next eight years and there are quotes recorded from someone who lived next door to the warehouse. The neighbour alleges that Gibson used to charge 6d a head "to see the body… and as a child I saw the coffin reared up on end in Gibsons…" After this it was transferred to the shop of John Marston, a plumber and glazier. The coffin was again reopened and a local artist, Thomas Underwood, made a pencil sketch of the body. Unfortunately this second opening of the coffin was to prove a disaster to the preservation of the body. Mrs Marston spoke of the body being "mummified, looking but very little changed but soon changing much." There were many reports of people seeing the body then becoming ill and Marston was anxious to be rid of it. Marston applied to put the body in his own family vault at St Philip’s church, but permission was refused.

Desperate to be rid of the body, Marston spoke of his problem to a visiting book-seller, Mr Nott. Mr Nott of course knew exactly who Baskerville was and as a book-seller perhaps better appreciated what he had done for the printed page. He said that he would be honoured if Baskerville’s remains could be placed in his family vault at Christ Church if they could work out a way to get them there. Fortunately Marston had a useful contact in a Mr Barker who was not only an intimate friend but was also a Church Warden of Christ Church. Seeing a way out of his predicament Marston immediately put his case to his friend who agreed that the situation was untenable and something must be done "indeed, I keep the keys and at such time of the day they are on the hall table." Quick to take a hint, Marston called at Mr Barker’s house to find that when the butler opened the door the keys were indeed on the hall table. The butler informed him that Mr Barker was not at home and turning round, left the room leaving Marston in the hall. Marston quickly took the keys and with the aid of a hand barrow covered with a green baize cloth, moved the body to a place in Mr Nott's vault. A notice was then inserted in a Birmingham paper that Baskerville’s body had been buried between two pools near Netherton, beyond Dudley.

In 1892 a man called Talbot Baines Reed said in a letter that the mystery of Baskerville’s whereabouts ought to be solved as not everybody believed the notice. A check by churchwardens and others revealed that the last vault was indeed full and they discovered Baskerville’s lead coffin with his name on it in his own type behind a double layer of brick-work instead of the usual stone tablet. The coffin was opened, inspected and then quickly reinterred and cemented in. A plaque bearing the words ‘In these catacombs rest the remains of John Baskerville, the famous Printer’ was placed on the outside of the church.

However, in 1890 the church was demolished to make way for shops and administrative buildings. A few years ago these too were demolished and a grassy area* with a walk, and a flight of steps called Christ Church Passage is all that now remains. The bodies in the vaults were removed and Baskerville’s body was reinterred in the Church of England cemetery in Warstone Lane in a vault under the chapel. For an atheist, poor Baskerville seemed to be coming acquainted with a variety of holy places. The tablet was placed at the entrance to the vault but eventually this chapel too was demolished and the entrance blocked up to deter vandals. The tablet is now hidden behind the wall.

So this is where Baskerville’s body finally finished its travelling. Perhaps he would have been pleased to know there was no longer a holy building over him. He did not want to be buried in consecrated ground and although a vault is to all intents and purposes consecrated, at least there is no church or chapel standing over him to add insult to injury.

Just as his typeface is now recognized as one of the greatest ever designed, so his body is more or less where he would want it, in a place where there is no church. Perhaps he would have been happy about this as it proves that if you keep persevering, you will eventually get what you want. This was John Baskerville to the letter.

* Since paved in the redevelopment of Victoria Square.

Works cited

- Allen. "Story of the Book"

- Chappell, Warren. "A Short History of the Printed Word." New York: New York Times, 1970

- Pardoe, F. E. "In Praise of John Baskerville" S. Lawrence Fleece, 1994

- Perfect, Christopher, and Austin, Jeremy "The Complete Typographer" 30 Oct 1992.

|

|

| Baskerville - John Baskerville |

|